Bycatch in fishing nets has led to a 92% fall in the vaquita population. This species now number approximately ten animals.

Bycatch in fishing nets has led to a 92% fall in the vaquita population. This species now number approximately ten animals.

What is Extinction?

Extinction is the disappearance, forever, of an entire species.

According to the IUCN Red List a species or subspecies is considered Extinct (EX) when there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. A species or subspecies is presumed Extinct when exhaustive surveys in known and expected habitat have failed to record a single individual.

Distinct populations can also become locally extinct. A single species is often made up of several separate populations and one population may be eradicated whilst others continue to live. For example, the North Pacific gray whale population in the eastern North Pacific is considered healthy, but the western population is critically endangered.

Extinction is a natural phenomenon, but current rates of extinction are much higher than historic ‘background rates.’ The lifespan of a species varies depending on a number of factors such as body size and geographic range. Many cetacean species are assessed to have survived between 5 and 30 million years. Today’s increased rates of extinction are due to human activities and associated habitat disruption and climate change.

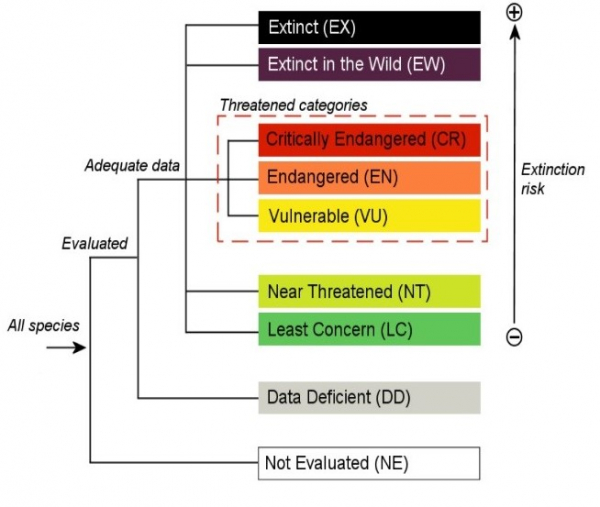

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, assesses the conservation status of most plant and animal species, some subspecies, and some subpopulations. They use a rigorous approach to assess all available data for each species against defined criteria, and classify each into one of the IUCN Red List status categories:

|

Structure of IUCN Red List Categories Structure of IUCN Red List Categories |

The ‘Threatened’ categories include only species assessed as being Vulnerable, Endangered or Critically Endangered. Cetacean Red List assessments are produced, and regularly updated, by the Red List Authority of IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Cetacean Specialist Group and are published on the IUCN Red List website. Assessing the status of a species, and keeping that assessment up to date, is important because it allows prioritisation of species and populations that require urgent conservation measures, and the ability to track changes in status over time.

Extinction and Cetaceans

Red List assessments are updated regularly and conservation status changes. The most up to date information on the status of cetaceans is available on the IUCN Red List website, or the IUCN Cetacean Specialist Group website.

As of December 2020, approximately 25% of whale, dolphin and porpoise species were classified as threatened (Critically Endangered, Endangered or Vulnerable). A further 10% were classified as ‘Data Deficient,’ meaning it is very difficult to assess whether a species is threatened because not enough information is available.

The baiji or Yangtze River dolphin, a freshwater species found only in the Yangtze River, was declared extinct in 2007. Fishing and industrial activity are two of the main factors in the baiji’s population decline. It is widely thought to be the first dolphin species driven to extinction by human activity.

In 2016, the Scientific Committee of the IWC warned that, ‘without immediate action the vaquita will be gone – the second entirely preventable extinction we have witnessed in the last ten years.’ The vaquita is a small porpoise found only in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Bycatch in illegal fishing nets has reduced its population by 92% in 20 years. The population is now estimated to number only around ten animals.

IWC Extinction AlertsIn 2023, the IWC launched a new initiative to publish Extinction Alerts. The Scientific Committee, supported by the Conservation Committee, had reached the sombre conclusion that a louder and more public mechanism was required to voice extinction concerns for an increasing range of cetacean species and populations. The first statement was published in August 2023. It aimed to encourage wider recognition of the warning signs of impending extinctions, and to generate support and encouragement at every level for the urgent actions needed to save the vaquita. The statement said:

“The extinction of the vaquita is inevitable unless 100% of gillnets are substituted immediately with alternative fishing gears that protect the vaquita and the livelihoods of fishers. If this doesn’t happen now, it will be too late.”

Read the Scientific Committee's Extinction Alert: Statement of Concern for the vaquita. |

Whaling, near-extinction, and the role of the IWC

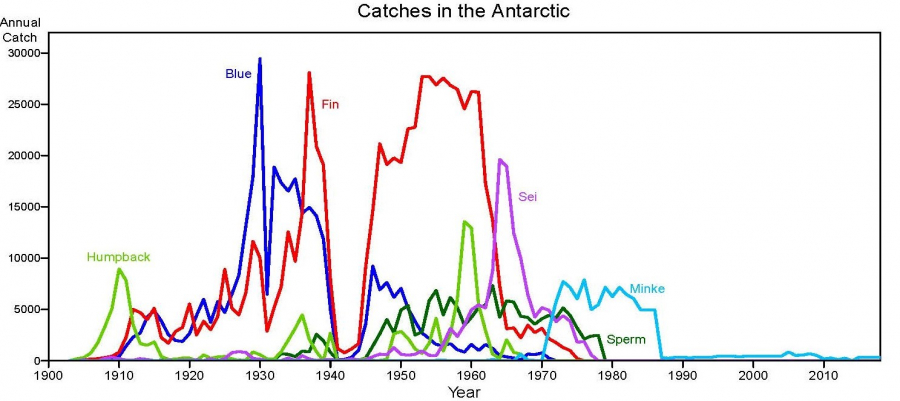

The early twentieth century saw industrialisation of whaling with technological advances including mechanised harpoons and factory ships. This led to a large increase in the number of whales that could be caught and processed, first in the Northern Hemisphere and then in the Southern Hemisphere, including Antarctic waters which were previously inaccessible. The focus of whaling activity moved to the Antarctic because many whale populations in more accessible regions had been hunted down to such small populations that the effort involved in finding them made the activity uneconomical.

Industrialisation also increased the number of different species that could be targeted. Blue whales in particular had previously been too fast to catch and too large to process. This all changed in the early twentieth century.

Records show that 195 whales were killed in the Antarctic in 1904. In 1931, 37,000 whales were killed in this region, the majority of them blue whales. The Antarctic blue whale population is estimated to have fallen from a pre-hunting level of 200,000-300,000 to less than 400 animals. Other species and populations also suffered rapid declines. After several attempts at international regulation, the IWC was formed in 1946 with the mandate to ‘manage the whaling industry and conserve whale stocks’ (populations).

Source: the IWC Catch Database, 2021

Methods of regulation evolved over time as knowledge increased, lessons were learnt, and more robust approaches were developed. These included measures to estimate population size, structure and trends, and implementation of quotas and management measures.

As scientific understanding increased and the unsustainable impact of industrial whaling activity became clearer, more restrictions were introduced for different species and populations. These included restricted whaling seasons and areas, bans on hunting mothers, calves and juveniles, sanctuaries, and in some cases moratoriums on hunting for a whole species or populations. In 1986, a global moratorium was introduced on all commercial whaling for large whale species. It remains in place today.

In the 21st century, other human activities are generally considered to pose the greatest risks to cetacean populations.

21st century threats to cetaceans

Work to calculate the size and conservation status of whale populations shows encouraging signs of recovery for many populations that shrank during the industrial whaling era. Some, including Southern right whales and humpback whales, are increasing at rapid rates. But recovery is not universal. For example, North Atlantic right whales and western North Pacific gray whales each number just a few hundred animals. All of today’s major concerns are related to human activity.

The world’s human population has roughly trebled from 2.5 billion in 1950 to over 7.5 billion in 2020. Human activities and impacts have also expanded, including in the marine environment. Below are the threats to cetaceans considered most significant today.

- Entanglement and bycatch: over 300,000 whales, dolphins and porpoises are estimated to die in fishing gear each year. This is considered the greatest immediate threat to cetaceans. It is the main driver of decline for the critically endangered vaquita and the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, and played a significant role in the extinction of the baiji. It is also one of the primary drivers of decline for many coastal cetaceans.

Ship strike, Bonaire. Image: Kalli de Meyer

Ship strike, Bonaire. Image: Kalli de Meyer

- Ship strikes: as human populations and marine transport increase, so does the risk of ships colliding with whales. Ship strikes are preventing the recovery of North Atlantic right whales and are known to be negatively impacting many other populations as well.

- Habitat degradation: habitat degradation encompasses many elements including construction of ports or bridges, pollution, marine traffic, underwater noise and coastal or offshore industry. Often the impacts of these multiple habitat changes compound one another, and their cumulative impacts are difficult to measure. For example, habitat degradation may lead to decreased feeding opportunities; stress from lost feeding or continued noise exposure may render cetaceans more vulnerable to disease. Some of the main causes of habitat degradation are:

- Chemical pollution: chemical pollutants, beyond poisoning the animals, are known to interfere with the hormone system of cetaceans and other species, increasing susceptibility to disease and reducing rates of reproduction.

- Marine debris: includes a wide range of materials, from glass and metal to lost or abandoned fishing gear. There is growing evidence that the ingestion of plastics is a significant problem for some cetaceans and there are also concerns about entanglement in lost or discarded nets and other enduring materials that can potentially ensnare cetaceans. Plastics also break down into smaller particles known as microplastics which can be passed from prey to predator with as yet unknown consequences.

- Ocean noise: cetaceans rely on sound. It is their primary sense, essential for foraging, migration and reproduction. Increasing levels of noise from shipping, seismic exploration, military activity, and drilling and construction can impact on both behaviour and physiology.

- Chemical pollution: chemical pollutants, beyond poisoning the animals, are known to interfere with the hormone system of cetaceans and other species, increasing susceptibility to disease and reducing rates of reproduction.

- Climate change: Climate change is affecting cetaceans and the broader ecosystem all over the planet. Most notably at the poles, melting sea ice is changing the distribution of the fish

and crustaceans that many whales and dolphins feed on, and opening new shipping lanes and fishing grounds, presenting new threats to cetaceans in those areas. Melting ice caps in the Himalayas are changing river flows in Asia as well as monsoon patterns in the Arabian Sea. These changes are likely to force cetaceans to change their feeding and migration patterns as they seek food.

- Disease: Disease remains a persistent threat, and at various times has been the cause of mass cetacean die-offs with population-level impacts. Human activities and

environmental factors, including pollution, are believed to contribute to disease, and in conjunction with the cumulative impacts of many of the threats listed above, disease

may play an even greater role in ‘tipping’ vulnerable populations over the edge towards extinction.

What the IWC does to prevent extinctions

Conservation of whale populations has been central to the IWC mandate since its formation in 1946. Since then, the IWC has brought together some of the most respected whale and dolphin scientists in the world each year, to discuss sustainable management of cetacean species and populations.

Today, the IWC’s Scientific Committee includes around 200 of the world’s leading experts in cetacean biology, behaviour, population size and structure, taxonomy, genetics, health and many other fields. This research underpins the work of the IWC, helping to understand and assess threats and prioritise actions. The Scientific Committee collaborates closely with the IWC’s Conservation Committee, another expert group, working to turn research and recommendations into tangible actions at every level, from global to local.

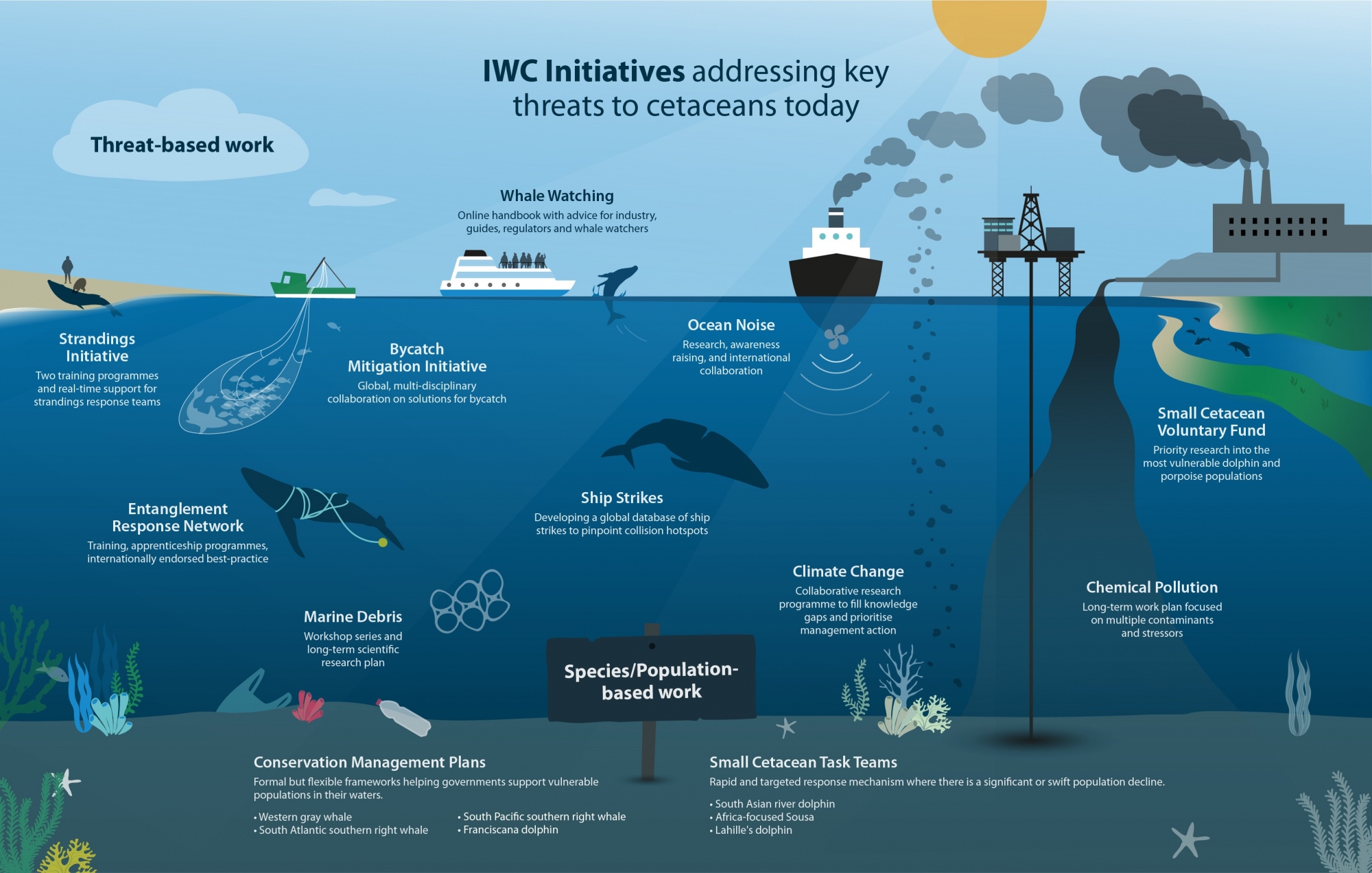

As the threats to cetaceans have changed, the IWC work programme has evolved and expanded in order to understand and address them.

Current initiatives and programmes include:

- Global Whale Entanglement Response Network: this programme began in 2011. A technical advisor coordinates the work of an expert panel, available to provide near real-time advice to teams dealing with entanglements around the globe, as well as hosting training workshops. To date the workshops have taught safe and effective entanglement response skills to over 1200 participants from more than 30 countries and this initiative has provided a general blueprint for other IWC work programmes.

- Bycatch Mitigation: in 2016 the Commission endorsed a Bycatch Mitigation Initiative (BMI). This programme is led by a coordinator and also has a multi-disciplinary Expert Panel. The BMI is working to raise awareness of the solutions available to monitor and mitigate cetacean bycatch, including through a capacity building initiative and pilot projects in a number of locations around the globe, implementing both proven and novel bycatch solutions, and with the potential to be scaled up.

- Strandings Response: the IWC Strandings Initiative is also supported by a coordinator and an Expert Panel. This panel provides real-time advice and support to teams dealing with strandings around the globe, and is also leading an international effort to harmonise and standardise stranding response protocols.

- Mitigation of Ship Strikes: Since 2007 the IWC has maintained a global Ship Strikes database which collates information about where ship strikes take place and which species and types of vessels are involved. The information is used to map collision hotspots and identify priority action areas where high collision numbers and endangered populations coincide. This work leads to the introduction of mitigation measures, for example diverting shipping lanes and introducing speed limits in specific areas.

- Conservation Management Plans (CMPs): collaboration is vital to success in conservation efforts for migratory animals. CMPs provide a framework for national governments and other stakeholders to work together on measures to protect vulnerable populations.

- Small Cetacean Task Teams: While CMPs are long-term programmes hosted by governments, Small Cetacean Task Teams aim to provide rapid and targeted responses to situations where significant and swift population decline is happening, and a real threat of extinction exists at either the global or individual population level.

- Sanctuaries: Two Sanctuaries are currently designated by the International Whaling Commission. The first of these, the Indian Ocean Sanctuary, was established in 1979 and covers the whole of the Indian Ocean south to 55°S. The second was adopted in 1994 and covers the waters of the Southern Ocean around Antarctica.

Why mitigation measures don’t always work

In some cases, the removal of a single threat is all that is needed to halt and even reverse population declines. This appears to be the case for many populations of humpback whales and Southern right whales that have increased rapidly in the years since commercial hunting stopped.

But most threats cannot be ‘removed’ altogether. A number of challenges face those who seek to address them:

|

Collaboration and ingenuity are required to overcome these challenges. Collaboration must move beyond conservationists and governments to better understand and incorporate the ‘human dimension’ of economics and livelihoods. Ingenuity and innovation are essential to develop alternative fishing gears, low-cost surveillance and enforcement strategies, or safer and quieter shipping practices. These collaborations and innovations are possible and are becoming more common, but they are not easy. Funding and robust international frameworks are required to support them.

Reasons for Optimism

It is easy to conclude that the solutions are too difficult, or so much damage has already been done that action now is useless. These thoughts are understandable but there is ample of evidence to show that this is not true.

|

Perhaps more than any other species, the blue whale is recognised as returning from the brink of extinction. These are the largest mammals ever to live and yet the early twentieth century saw their Antarctic population shrink from 200,000-300,000 to less than 400 animals. The first protections for blue whales were introduced in the 1960s. In 1998, a survey assessed the population to have risen to approximately 2,300 animals. A new assessment is currently underway and anticipated to show a slow but steady continued increase.

The recovery of humpback whales is another success story. Whaling reduced the global population from approximately 140,000 to 7,000. Today there are estimated to be over 100,000 humpbacks worldwide, with some populations fully recovered to pre-whaling numbers. |

None of the threats facing cetacean populations today are one-dimensional and none are easy to address, but past events give reasons for optimism, and optimism brings invaluable energy to every effort to collaborate and innovate.

What you can do to help whales, dolphins and porpoises

Everyone can play a role in addressing the threats to cetaceans, their marine habitat and the environment more generally. Here are some examples:

- Buy fish that displays ‘ecolabel certification’ to show it has been sustainably fished. There are many national and regional schemes such as the blue tick label.

- Dispose of waste with care and avoid single-use plastics which often end up in the ocean as marine debris. This poses several different threats to cetaceans and many other species.

- Check the Whale Watching Handbook before organising a trip. This gives information on how to choose a responsible operator and how to get the most from your trip.

- If you live near the coast, join a local beach clean up. Every year, volunteers all over the world collect thousands of tonnes of rubbish that might otherwise end up in the ocean. Whether or not you live near the coast, you can join World Clean Up Day, a civic movement, uniting 180 countries to improve the environment with a mass clean up.

- Think more generally about ways you can reduce your energy consumption and carbon emissions. There are lots of national and local initiatives to help individuals play a role in tackling climate change. Depending on where you live, these can range from car sharing and tree planting schemes to carbon-neutral banking and grants for energy-saving home improvements.

- Share your knowledge! Raising awareness is a crucial step in any threat mitigation strategy.