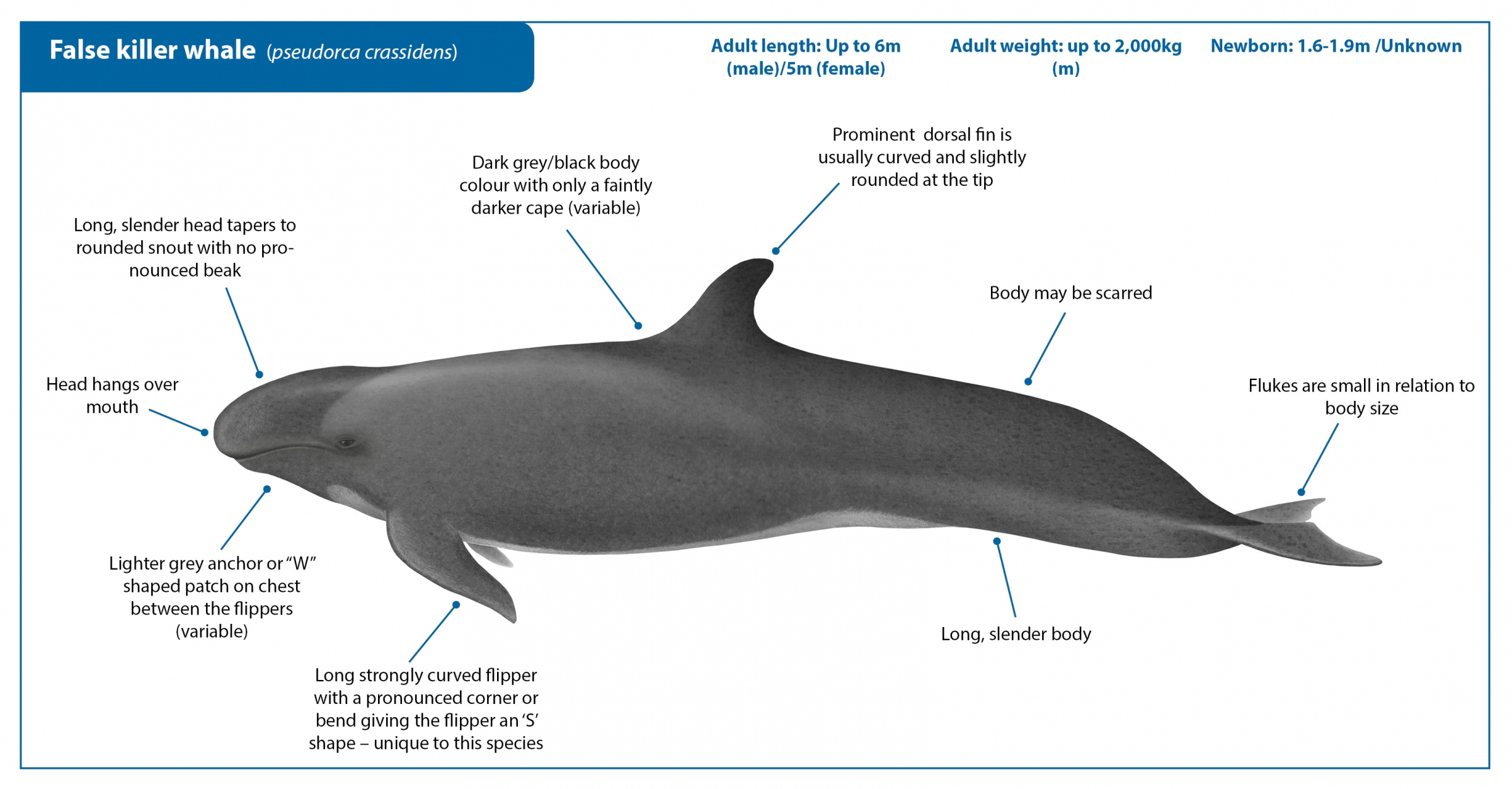

False killer whales are so named because the shape of their skulls, not their external appearance, is similar to that of killer whales. Reaching up to 6 meters in length, the species behaves much more like a smaller dolphin, swimming quickly, occasionally leaping, and sometimes approaching whale watching vessels.

References

Show / Hide References

- Baird, R. W. False Killer whale, Pseudorca crassidensin Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (eds W. Perrin, B. Wursig, & J.G.M. Thewissen) 405-406 (Elsevier, 2009).

- Taylor, B. L. et al. Pseudorca crassidens in IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (http://www.iucnredlist.org/det... Consulted on 9 October 2017, 2008).

- Weir, C. R. et al. False killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens) sightings in continental shelf habitat off Gabon and Côte d'Ivoire (Africa). Marine Biodiversity Records 6, doi:10.1017/S1755267213000389 (2013).

- Baird, R. W. False Killer whale, Pseudorca crassidens in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals Vol. Third Edition (eds B Würsig, J.G.M. Thewissen, & K.M. Kovacs) 701-705 (Academic Press, Elsevier, 2017 ).

- Anderson, R. C. Cetaceans and tuna fisheries in the Western and Central Indian Ocean. International Pole and Line Federation Technical Report 2, 133 (2014).

- Baird, R. W. & Gorgone, A. M. False Killer Whale Dorsal Fin Disfigurements as a Possible Indicator of Long-Line Fishery Interactions in Hawaiian Waters. Pacific Science 59, 593–601 (2005).

- Passadore, C., Domingo, A. & Secchi, E. R. Depredation by killer whale (Orcinus orca) and false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens) on the catch of the Uruguayan pelagic longline fishery in Southwestern Atlantic Ocean. ICES Journal of Marine Science 72, 1653-1666, doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsu251 (2015).

- Zaeschmar, J. R. et al. Occurrence of false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) and their association with common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) off northeastern New Zealand. Marine Mammal Science 30, 594-608, doi:10.1111/mms.12065 (2014).

- Baird, R. W. The Lives of Hawaii's Dolphins and Whales: Natural History and Conservation. 352 (University of Hawai'i Press, 2016).

- Baird, R. W. et al. False killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) around the main Hawaiian Islands: Long-term site fidelity, inter-island movements, and association patterns. Marine Mammal Science 24, 591-612, doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00200.x (2008).

- Ferreira, I. M., Kasuya, T., Marsh, H. & Best, P. B. False killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) from Japan and South Africa: Differences in growth and reproduction. Marine Mammal Science 30, 64-84 (2014).

- Photopoulou, T., Ferreira, I. M., Best, P. B., Kasuya, T. & Marsh, H. Evidence for a postreproductive phase in female false killer whales Pseudorca crassidens. Frontiers in zoology 14, 30 (2017).

- Kirkman, S. P., Meyer, M. A. & Thornton, M. False killer whale Pseudorca crassidens mass stranding at Long Beach on South Africa's Cape Peninsula, 2009. African Journal of Marine Science 32, 167-170 (2010).

- Haro, D. et al. A new mass stranding of false killer whale, Pseudorca crassidens, in the Strait of Magellan, Chile. REVISTA DE BIOLOGIA MARINA Y OCEANOGRAFIA 50, 149-155 (2015).

- Jefferson, T. A., Webber, M. A. & Pitman, R. L. Marine Mammals of the World: a Comprehensive Guide to their Identification. Second Edition. (San Diego: Academic Press, 2015).

- Foltz, K. M., Baird, R. W., Ylitalo, G. M. & Jensen, B. A. Cytochrome P4501A1 expression in blubber biopsies of endangered false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) and nine other odontocete species from Hawai‘i. Ecotoxicology 23, 1607-1618, doi:10.1007/s10646-014-1300-0 (2014).

- Reeves, R. R., Leatherwood, S. & Baird, R. W. Evidence of a possible decline since 1989 in false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) around the main Hawaiian Islands. Pacific Science 63, 253-261 (2009).