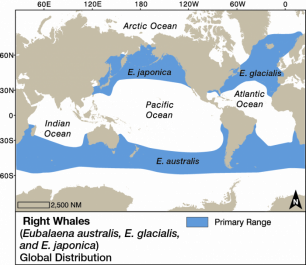

The species’ name originates from the fact that historically whalers considered right whales the “right” whale to hunt: they yielded high quantities of oil and baleen, and were easy to catch and process because they were found close to shore, swam slowly, and floated when they were dead. As a consequence, they were hunted to the brink of extinction almost everywhere that they occurred. North Atlantic right whales and North Pacific right whales have never recovered from the centuries of whaling that reduced their numbers, but most southern right whale populations are now on the increase. There are three recognized species of right whales that occur in different parts of the world, as shown in the map below. These are Southern right whales (Eubalaena australis), North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) and North Pacific right whales (Eubalaena japonica)1. While they differ genetically, and in conservation status, they do not differ significantly in their external appearance. Today they are the focus of many whale watching ventures in the southern hemisphere, where they can often be viewed from shore as well as from boats.

Right whale blow and surfacing pattern

Right whale blow and surfacing pattern

References

Show / Hide References

- Committee on Taxonomy, List of marine mammal species and subspecies. Society for Marine Mammalogy, www.marinemammalscience.org, consulted on 11 October 2017. 2017.

- Kenney, R.D., Right whales: Eubalaena glacialis, E. japonica, and E. australis, in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, B. Würsig, J.G.M. Thewissen, and K.M. Kovacs, Editors. 2017 (in press), Academic Press, Elsevier: San Diego.

- Baumgartner, M.F. and B.R. Mate, Summertime foraging ecology of North Atlantic right whales. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2003. 264: p. 123-135.

- Brown, M.W., et al., Sighting heterogeneity of right whales in the western North Atlantic: 1980-1992. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 2001. Special Issue 2: p. 245-250.

- Rowntree, V.J., R.S. Payne, and D.M. Schell, Changing patterns of habitat use by southern right whales (Eubalaena australis) on their nursery ground at Península Valdés, Argentina, and in their long-range movements. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 2001. Special Issue(2): p. 133-143.

- Frasier, T.R., et al., Sources and rates of errors in methods of individual identification for North Atlantic right whales. Journal of Mammology, 2009. 90(5): p. 1246–1255.

- Baumgartner, M.F. and B.R. Mate, Summer and fall habitat of North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) inferred from satellite telemetry. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2005. 62(3): p. 527-543.

- Mate, B.R., et al., Coastal, offshore, and migratory movements of South African right whales revealed by satellite telemetry. Marine Mammal Science, 2011. 27(3): p. 455-476.

- Knowlton, A.R., et al., Monitoring North Atlantic right whale Eubalaena glacialis entanglement rates: a 30 year retrospective. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2012. 466: p. 293-302.

- van der Hoop, J.M., et al., Predicting lethal entanglements as a consequence of drag from fishing gear. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2017. 115(1–2): p. 91-104.

- Laist, D.W., et al., Collisions between ships and whales. Marine Mammal Science, 2001. 17(1): p. 35-75.

- Hoop, J.M., et al., Vessel strikes to large whales before and after the 2008 Ship Strike Rule. Conservation Letters, 2014.

- Fazio, A., M. Bertellotti, and C. Villanueva, Kelp gulls attack Southern right whales: a conservation concern? Marine Biology, 2012. 159(9): p. 1981-1990.

- Reeves, R.R. and T. Smith, A taxonomy of world whaling, in Whales, whaling, and ocean ecosystems, J. Estes, et al., Editors. 2006, University of California Press: Berkeley, California. p. 82-101.

- Wade, P.R., et al., The world's smallest whale population? Biology Letters, 2010. 7: p. 83-85.

- Pace, R.M., P.J. Corkeron, and S.D. Kraus, State–space mark–recapture estimates reveal a recent decline in abundance of North Atlantic right whales. Ecology and Evolution, 2017.

- Cooke, J., V. Rowntree, and R. Payne, Estimates of demographic parameters for southern right whales (Eubalaena australis) observed off Península Valdés, Argentina. J. Cetacean Res. Manage, 2001. Special Issue(2): p. 125-132.

- Groch, K., et al., Recent rapid increases in the right whale (Eubalaena australis) population off southern Brazil. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals, 2005. 4(1): p. 41-47.

- Argüelles, M.B., et al., Impact of whale-watching on the short-term behavior of Southern right whales (Eubalaena australis) in Patagonia, Argentina. Tourism Management Perspectives, 2016. 18: p. 118-124.