Click here to read descriptions of the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Villages

1. Introduction: Information on the History, Culture and Nutritional Significance of the Hunts

The People of the Ice Whale

Subsistence whaling is a way of life for the Inupiat and Siberian Yupik people who inhabit the Western and Northern coasts of Alaska. From Gambell to Kaktovik, the bowhead whale has been our central food resource and the center of our culture for millennia, and remains so today.

Anthropologists describe our Native Alaskan economy as a “mixed economy,” in which our households engage in (1) cash-based market exchange, (2) non-cash subsistence activities and exchange, and (3) culturally embedded social relationships sustained by flows of wild food and other resources.[1]

It is very expensive to purchase food in the stores of our villages and sometimes food is not even available to buy. The average price for a pound of beef (when it is available) may be $10 to $20 or more. Gasoline costs between $7 and $10 per gallon. Compounding the problem of limited availability of supplies is the lack of jobs in our remote, isolated communities. With very limited employment opportunities, many people do not have the means to purchase groceries from the store. We rely on what we harvest from nature, especially the ocean, to feed our families—most importantly the bowhead whale. There are no other options to sustain our bodies.

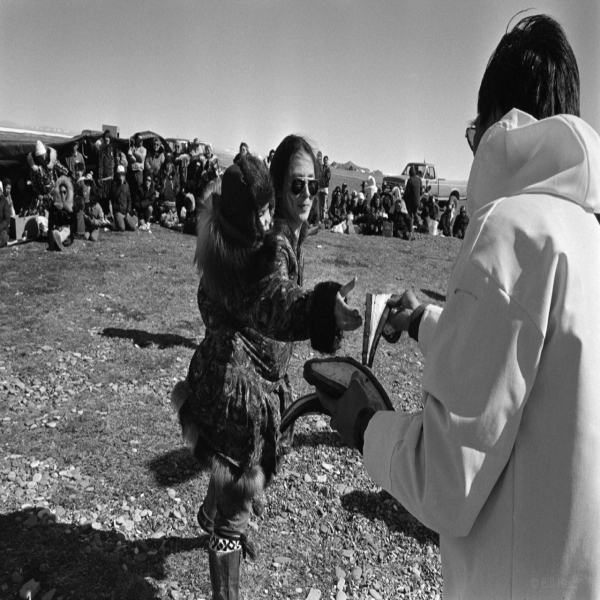

In Point Hope, the community gathers to celebrate and share the successful Spring bowhead whale harvest. A successful harvest means that everyone will be fed.

In Point Hope, the community gathers to celebrate and share the successful Spring bowhead whale harvest. A successful harvest means that everyone will be fed.

Our whale harvest brings us an average of approximately 1.1M to 2M pounds of food per year (12-20 tons x 45-50 whales), which our whaling captains and crews share freely throughout our whaling communities and beyond to relatives and other members of Alaska’s Native subsistence community in other Native villages. For perspective, replacing this highly nutritious food with beef would cost our subsistence communities approximately $11M - $30M per year.

The bowhead harvest is shared throughout the whaling communities. Here, at the ancient Messenger Feast in Utqiagvik, people have gathered from across the Alaskan Arctic toparticipate in Kivgiq, a celebration rooted in Time Immemorial. Picture: Bill Hess.

After landing their first bowhead of the season, the Iceberg 14 crew, captained by Jason Ahmaogak, is honored to feed the community of Wainwright. Over a period of hours, villagers

After landing their first bowhead of the season, the Iceberg 14 crew, captained by Jason Ahmaogak, is honored to feed the community of Wainwright. Over a period of hours, villagers

file through to receive the first of many communal meals this bowhead will provide. Over the past year, Jason and his crew have spent many thousands of dollars and countless hours in

preparation for the hunt, yet they give it all away, charging not one dollar in return. Picture: Bill Hess.

As important as whale is to keeping our bodies healthy, this subsistence harvest also feeds our spirit. The entire community participates in the activities surrounding the subsistence bowhead whale harvest, ensuring that the traditions and skills of the past are carried on by future generations. Portions of each whale are saved for celebration at Nalukataq (the blanket toss or whaling feast), Thanksgiving, Christmas, and potlucks held during the year. Our whaling captains and wives are equal members of a team, each having specific responsibilities during preparation, harvest, and sharing. They are humble and respectful people, ever-aware of their responsibilities to those who depend on their ability, integrity, and generosity. They are also aware of their responsibility to respect and honor the whales that give themselves to our communities. It is shameful to waste a whale and it is unheard of for a whaler to refuse to share what has been given to him. Sharing the whale is both an honor and an obligation.

A hunter in training, this Inupiat youth participates in the Blanket Toss in Utqiagvik as part of Nalukataq, the celebration hosted by each successful whaling captain. Picture: Jenny Evans.

A hunter in training, this Inupiat youth participates in the Blanket Toss in Utqiagvik as part of Nalukataq, the celebration hosted by each successful whaling captain. Picture: Jenny Evans.

Today, as our world changes with lightning speed, the whale, the harvest, and the sharing are the constants that sustain our bodies and our spirits, that bind our families and communities together, that define our social and leadership roles, that keep our children in school, that allow our elders to pass their knowledge to our youth, that teach us patience, perseverance, interdependence, and generosity. They strengthen our subsistence community across Alaska. They provide wisdom and insight. They give us hope. The whale and the harvest are our way of life, our cultural identity, and a means for survival. The Spirit of the Whale provides now, as it did has throughout history, for our people, and lives within each of us.

Baby on her back, Pikok Tuzroyluk accepts a slice of flipper from whaling captain Elijah Rock at the three day June feast and celebration of Qagruq in Point Hope. Picture: Bill Hess.

Baby on her back, Pikok Tuzroyluk accepts a slice of flipper from whaling captain Elijah Rock at the three day June feast and celebration of Qagruq in Point Hope. Picture: Bill Hess.

Blessing ceremony to open the three day celebration of Qagruq in Point Hope. Picture: Bill Hess.

Blessing ceremony to open the three day celebration of Qagruq in Point Hope. Picture: Bill Hess.

For anyone visiting our remote communities, our “need” for the bowhead whale is readily apparent. To satisfy IWC requirements that we “prove” our need, we have worked with Stephen R. Braund and Associates in Anchorage Alaska since 1983 to provide documentation and a quantification of our reliance on the bowhead whale. These and other reports submitted to the IWC on our need for the bowhead whale are found in:

1979: Report of the Panel to Consider Cultural Aspects of Aboriginal Whaling in North Alaska, Meeting in Seattle, WA, February 5-9, 1979 under the auspices of the International Whaling Commission.

1980: Interim Report on Aboriginal/Subsistence Whaling of the Bowhead Whales by Alaskan Eskimos, U.S. Department of the Interior.

1982: Aboriginal/Subsistence Whaling (with special reference4 to the Alaska and Greenland fisheries),(RIWC S14 (1982)).

1983: Report on Nutritional, Subsistence, and Cultural Needs Relating to the Catch of Bowhead Whales by Alaska Natives, U.S. Government Report, Stephen R. Braund, (IWC/TC/35/AB3).

1988a: Quantification of Subsistence and Cultural Need for Bowhead Whales by Alaska Eskimos, Stephen R. Braund and Associates, (TC/40/AS2).

1988b: Quantification of Subsistence and Cultural Need for Bowhead Whales by Alaska Eskimos, Braund, S.R., S. W. Stoker, J.A. Kruse, (TC/40/AS2).

1992: Subsistence and Cultural Need for Bowhead Whales by the Village of Little Diomede, Alaska, Stephen R. Braund and Associates, (IWC/44/AS2).

1994: Quantification of Subsistence and Cultural Need for Bowhead Whales by Alaska Eskimo – 1994 Update Based on 1992 Alaska Department of Labor Data, Stephen R. Braund and Associates, (IWC/46/AS6)

1997: Quantification of Subsistence and Cultural Need for Bowhead Whales by Alaska Eskimos: 1997 update based on 1997 Alaska Department of Labor Data, Stephen R. Braund, 1997, (IWC/49/AS/1)

2012: Quantification of Subsistence and Cultural Need for Bowhead Whales by Alaska Eskimos; 2012 Update Based on 2010 U.S. Census Data, Stephen R. Braund and Associates, (IWC/64/ASW 3)

2015: Quantification of subsistence need for bowhead whales by Alaska Eskimos: overview, Stephen R. Braund and Associates, (IWC/S15/ASW/11).

This extensive body of work is focused on the needs and usage within each of our AEWC villages. However, in recent years, social science researchers are beginning to recognize that our need for the bowhead whale is communal and that the bowhead whale plays a very significant role in sharing networks that bind us together, as families, communities, and a people. Our whaling captains and crews share the bowhead with all of us, whether we live within their village, in neighboring communities, or in other, more remote areas of the state. This emerging research on our subsistence sharing economy is reported in BurnSilver, et al., (2016) cited above, and in Description of Alaskan Bowhead Whale Subsistence Sharing Practices, Including an Overview of Whale Harvesting and Community-Based Need, Stephen R. Braund and Associates (2018).

Footnote:

[1] The Bowhead Whale Subsistence Harvest Is the Keystone of the Northern Alaskan Subsistence Economy BurnSilver S, Magdanz J, Stotts R, Berman M, Kofinas G (2016) Are mixed economies persistent or transitional? Evidence using social networks from arctic Alaska. American Anthropologist 118(1):121–129.

A hunter watches the ice edge and horizon for surfacing bowhead whales during the spring hunt. Picture: Jenny Evans.

2. The International Whaling Commission

Commercial whaling operations of the late 19th and early 20th centuries substantially reduced the size of the Bering Sea (also “Western Arctic” or “Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort Seas”) stock of bowhead whales. However, Aboriginal Subsistence harvests continued and were exempt from the IWC’s regulatory focus on commercial whaling until the 1970’s, when the increasingly popular “anti-whaling” campaign began to turn its focus to Aboriginal harvests, including Inupiat and Yupik hunting of the Bering Sea stock of bowhead whales.

We did not know of this international interest until, in 1977, the IWC acted to amend its Schedule, deleting the Aboriginal Subsistence exemption for right whales, which included the Bering Sea stock of bowhead whales. This action effectively eliminated, without prior notice or due process by the U.S. government, our nutritionally and culturally vital food harvest, practiced uninterrupted for thousands of years. The IWC’s rationale for this devastating decision was based on the Scientific Committee’s advice that the Bering Sea stock of bowhead whales numbered 600 to 2,000 animals, that strikes had increased to unsustainable levels (up to 100 per year) with a strike and loss rate of 50 percent, and that, therefore, the stock was likely in decline. The Scientific Committee also noted that the Commission might wish to take into consideration other factors such as aboriginal subsistence need that was beyond its purview.

Learning of this legal action after the fact, our whaling captains expressed their view to the U.S. government that the stock was much larger than estimated, and producing a large numbers of calves. Based on their traditional knowledge gained through generations of direct observation of bowhead whale migrations, behavior, and reproduction, they especially advised that bowheads were migrating past the scientist’s censusing station out of sight far offshore or under the ice. Accordingly, the Scientific Committee’s estimate of abundance would be biased low.

At a special meeting of the IWC convened in late 1977, the U.S. government submitted this proposal to the IWC, committed to undertake it and proposed a small quota to provide for subsistence need of the Alaska Eskimos. The IWC responded by setting a one-year quota of up to 18 strikes to land 12 whales. Subsequent research utilized acoustic monitoring which confirmed that whales were indeed passing out of sight of the censusing station and provided correction factors to account for these uncounted animals.

While the initial quotas set by the IWC were at a fraction of our nutritional and cultural need, they did initiate the development of a science-based management regime that led the IWC to gain confidence in U.S. domestic management of the bowhead hunt. Nonetheless, the reduced levels and need to annually defend the quota at IWC resulted in years of food shortages and extreme levels of stress in our communities as people struggled to feed their families, fearing arrest and imprisonment if the IWC’s rules were violated.

As the sea ice continues to vanish, the fall hunt has become increasingly important to the Inupiat and Siberian Yupik who rely on the bowhead whale for their survival. The traditions and social relations surrounding the harvest are timeless,

but hunters continuously adapt their techniques and methods as new technologies become available and environmental challenges arise.

3. Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission

The Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission was brought into being by the events of 1977. The whaling captains of the AEWC’s 11 villages created our not-for-profit organization. The AEWC represents us before the United States Government and the IWC. Whaling captains from the AEWC’s villages register each year to conduct the harvest. Each village elects a whaling captain to represent them on the AEWC Board of Commissioners, which conducts the business of the AEWC throughout the year and provides the representation needed to ensure the whaling captains’ ongoing right to continue the harvest. Representatives of the AEWC have attended every meeting of the IWC since 1977.

The AEWC manages the bowhead whale harvest through local tribal delegation of authority and U.S. federal delegation, co-management, and oversight. The AEWC’s management practices are a blend of long-standing tradition and modern regulation. Throughout history, whaling captains in each village have been a tight-knit group of cooperative hunters and community leaders, with each village following its own unique methods for harvesting and sharing.

As it has throughout our history, our management of the harvest begins with the health of our bowhead whale stock.

4. The Bering Sea Stock of Bowhead Whales

The bowhead whale, Balaena mysticetus, can reach a length of nearly 60 feet (over 17 meters), and weigh up to 80 tons. Bowheads feed on zooplankton, primarily krill and copepods. They filter these tiny crustaceans through their baleen, which can be over 12 feet (3.6 meters) long, the longest of any whale.

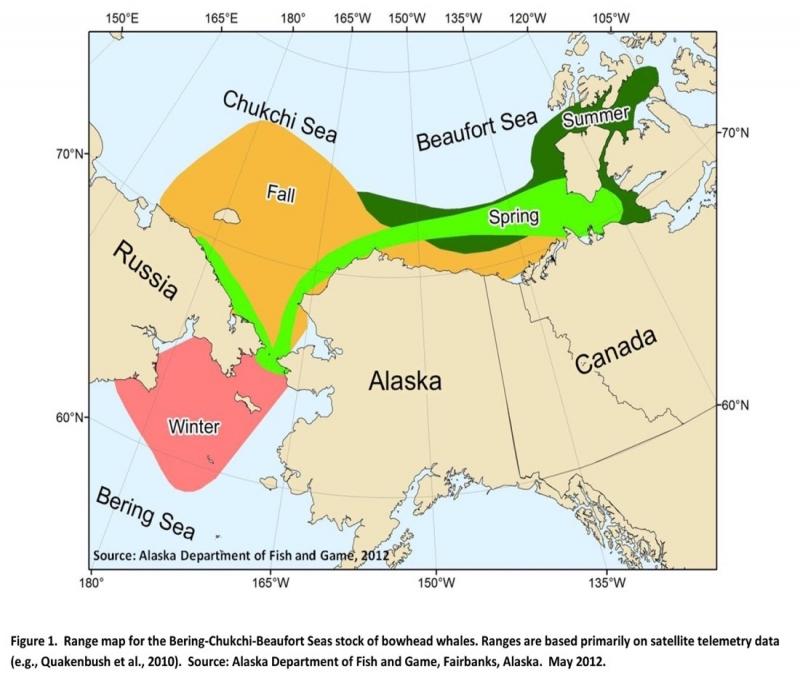

The Bering Sea stock is the world’s largest population of bowheads. Every spring the whales migrate from the Bering Sea, where they spend the winter, to their summering waters in the Canadian Beaufort Sea. Beginning in late March and early April, the whales travel through the open leads (breaks in the sea ice) along the coast. In August to October or November, they make the return journey to the Bering Sea.

A bowhead whale and her calf migrate along the ice edge. Picture: Bill Koski.

Bowhead whales, called aghveq in St. Lawrence Island Yupik and agviq in Inupiaq, are well adapted to navigating ice-covered seas. Their blowhole is surrounded by a hump of dense fibrous tissue, enabling them to break through ice up to a foot (30 cm) thick to breathe. Bowhead vocalizations range from brief grunts to complex songs, which change annually. Their calls may help to locate deep sections of ice blocking their path, and also to follow the movements of other whales.

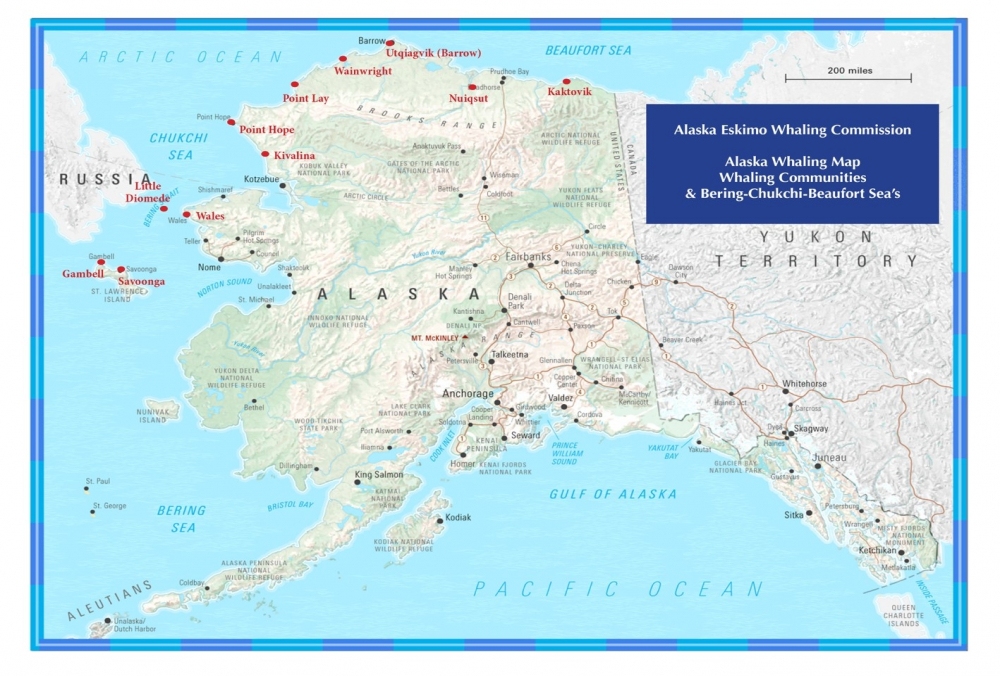

Migration route of the bowhead whale.

Migration route of the bowhead whale.

The late whaling captain Jonathan Aiken Sr, Kunuk, waits with his crew and umiaq at the ice edge five miles offshore from Utqiagivik for the bowhead they hope will come to them. Picture: Bill Hess.

As noted above, at the time of the IWC’s 1977 ban on the Alaskan Native bowhead whale subsistence harvest, the whaling captains of northern Alaska’s coastal communities, intimately aware of the decimation of the stock caused by decades of commercial whaling, nonetheless were confident that the stock was in good health, growing rapidly, and well able to support their small harvest.

The Rock Crew of Point Hope push their umiaq past polar bear footprints over very dangerous thin and cracked icein preparation to launch. Picture: Bill Hess.

Given the failure of early science efforts to count the whales, the whaling captains took it upon themselves to train western researchers about the behavior of migrating bowheads and jointly developed better tools for accurately counting them. Today, working with the North Slope Borough, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and other researchers, and employing state-of-the-art techniques, AEWC whaling captains participate in all aspects of research on bowhead whale biology and behavior. These ongoing research efforts, that blend western science techniques with local observation-based ecosystem understanding of the whale and its habitat, are the foundation for our management of this harvest.

Two whaling crews in traditional skin boats (umiak) follow a bowhead whale. Picture: Bill Hess.

The North Slope Borough Department of Wildlife Management, on behalf of AEWC, conducts a regular census of the bowhead whale. Population size and trend estimates are critical information that the AEWC and NOAA use to help set sustainable bowhead whale subsistence harvest levels through the IWC and its Scientific Committee. Key research efforts include an ice-based census, aerial surveys, photo identification, age estimation, stock structure/genetics, bowhead health assessment, and movements via satellite tagging.

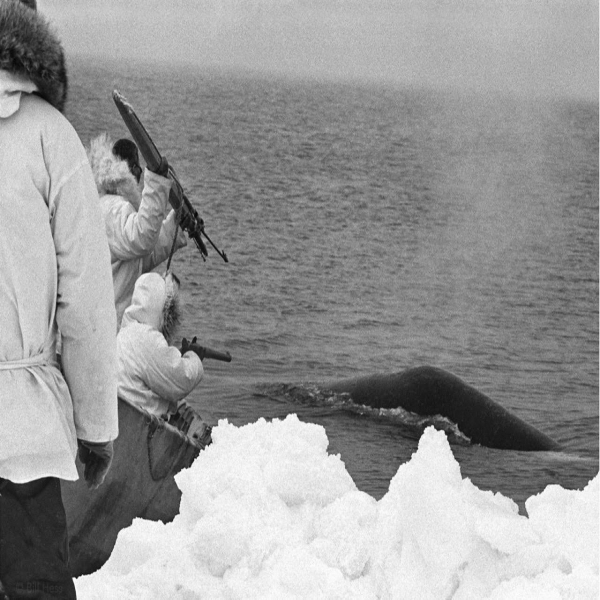

Kunuk raises his harpoon and darting gun, armed with a penthrite bomb. The moment after the harpoon attaches the float to the whale, Eli Solomon will follow with the shoulder gun. It will be an instant kill. Picture: Bill Hess.

Dancing for joy the traditional way, Iceberg 14 Captain Jason Ahmaogak welcomes his crew and the others who helped tow the first Iceberg 14 and Wainwright whale of the season to the ice edge, where it will be manually pulled onto the ice. Picture: Bill Hess.

5. Information on International and National Regulations

United States Law and Regulation

In the United States, the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling and the decisions of the IWC are implemented domestically through the U.S. Whaling Convention Act (16 U.S.C. 916 et seq.) and its regulations (50 CFR Part 230). Under the U.S. Whaling Convention Act, IWC Schedule provisions to which the United States has not objected shall become effective with respect to all persons and vessels subject to U.S. jurisdiction, and so, the U.S. Government overseas the AEWC’s subsistence harvest of bowhead whales in compliance with Schedule provisions pertaining to the bowhead whale subsistence hunt.

Iceberg 14 Captain Jason Ahmaogak oversees as crew members Jerry and Benjamin Ahmaogak prepare the rope and float for the hunt. Stanley Brower scans the lead for bowhead. Picture: Bill Hess.

Additionally, the United States regulates a broad range of human interactions with marine mammals through the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA, 16 U.S.C. 1371-1389) and its regulations (50 CFR Parts 216-229). The MMPA prohibits all “takes” of marine mammals, with certain defined exceptions. Alaska Native subsistence hunting of marine mammals is exempt from this prohibition (16 U.S.C. 1371(b)). However, when a marine mammal population or stock is judged to be “depleted” (see 16 U.S.C. 1362) or, like the bowhead whale, is listed as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.), the U.S. Government may oversee subsistence harvests and impose harvest limits (16 U.S.C. 1371(b)(3)).

Members from every Wainwright village crew and family pull together to pull a bowhead landed by the Iceberg 17 crew, captained by Walter Nayakik Sr. Picture: Bill Hess.

With Captain Walter Nayakik standing right behind him, 80 year-old elder George Agnassaga prays and gives thanks to the whale for giving itself to the crew and to God for the bounty. Picture: Bill Hess.

The flags of four successful whaling crews, Kunuk and his Aiken crew among them, fly over the spring whale feast of Nalukatak. Whalers give thanks for the meat and muktuk that will sustain them throughout the year. Picture: Bill Hess.

The NOAA-AEWC Cooperative Agreement

The whaling captains of northern Alaska united and formally incorporated the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission in 1981 and entered into a Cooperative Agreement with the U.S. Department of Commerce/NOAA. Authorized under Section 112 of the MMPA (16 U.S.C. 1382) and subject to NOAA’s federal oversight role, the Cooperative Agreement gives the AEWC the responsibility for local management of the subsistence whale harvest, including acting as the first line of civil enforcement of any violations of hunting regulations.

The AEWC hosts an Annual Whaling Captains' Convention to share knowledge and conduct business that pertainsto the continued harvest of the bowhead whale.

In 2013 the AEWC was honored to host IWC Chair Jeannine Compton of St. Lucia. Picture: Jenny Evans.

North Slope Borough scientists collect data to track the health of the Bering Sea stock of bowhead whale. Picture: Jenny Evans.

The AEWC works closely with NOAA throughout the year and reports to NOAA on the results of each spring and fall whaling season, including numbers of whales landed and struck but lost, and the size, sex, location and other details of the whales that were landed. This information is included in a report to NOAA and ultimately to the IWC, and is also used by the AEWC in its ongoing efforts to improve hunting equipment and techniques.

The AEWC and its whaling captains also participate actively in research programs designed to track the health of the Bering Sea stock of bowhead whales. AEWC whaling captains and crews assist researchers by placing the satellite tags used by scientists tracking the bowhead whale migration. Whaling captains, especially from the villages of Savoonga, Gambell, Utqiagvik, Nuiqsut, and Kaktovik, provide measurements and tissue samples from the whales they harvest. With the information and biological samples provided by the whaling captains, researchers continue to build an extensive body of knowledge on the population dynamics of this whale stock, continuously informing our understanding of its health.

A whaling crew assembles camp along the ice edge and prepares for the spring hunt. Utqiagvik, AK. Picture: Zak Melms.

As a wildlife management and conservation model, the NOAA-AEWC Cooperative Agreement has proven highly effective and today is internationally recognized as a “gold standard” in wildlife conservation.

6. Information on Hunting Methods

The Weapons Improvement Program (WIP)

For the Inupiat and Siberian Yupik peoples of the Arctic, the whale is a gift. We believe that each whale taken has made the decision to share itself with the captain and crew, so that they may share with others. Our whaling captains hold religious services before each harvest season. A prayer of thanksgiving is offered for the whale before it is towed to shore. Every whale is revered, remembered, and spoken of for years after it gives itself to the people. A fast and easy death for the whale is every hunter’s sincere wish and personal responsibility. Harpooners are known throughout the whaling community for their skill in deploying the hand-held darting gun and taking a whale quickly.

Hunters in Utqiagvik wait along the ice edge for passing bowhead whales. Picture: Jenny Evans.

A fast and efficient harvest is also a matter of life and death for our whaling captains and crews. We take our whales from small skiffs, either skin-covered umiaqs or aluminum boats, in ice-filled waters and on the open ocean, using hand-held weapons. The whales are larger than our vessels, and weather, ocean currents, and ice movement are sometimes unpredictable, making this an extremely dangerous hunt. As whaling captains we are responsible for the safety of our crew members. Every time we go out on the ice or the water to take a whale, we are risking our lives - and the lives of our crew members - to feed our families and communities. Given that loss of human life is an ever-present risk, our goal is to take each whale as quickly and efficiently as possible so we minimize our crews’ exposure to the dangers of wind, ice, and water.

When Yankee whalers brought black powder to the Arctic, our ancestors quickly adapted their hunting equipment to this new tool, a hand-thrown darting gun to replace the cold harpoons used throughout history. When the IWC introduced us to the new, more powerful explosive, penthrite, we immediately sought an opportunity to further adapt our equipment, to reduce the number of whales struck and lost, to reduce suffering of whales, and to increase safety for our hunters.

The AEWC’s whaling captains have adapted their equipment, utilizing the penthrite projectiles introduced by the IWC.

The Weapons Improvement Program encompasses the project undertaken by the AEWC, working with Dr. Egil Øen of Norway, to upgrade our hunting equipment, especially to implement the use of penthrite in the bowhead harvest. The objectives of the program are to: 1) develop and implement a projectile charged with penthrite for use in the hand-held darting gun; 2) improve the reliability and safety of the weapons, making the hunt as quick and as safe as possible; and, 3) to increase the efficiency of the harvest by reducing the number of whales that are struck but lost. Exploding projectiles, fired from a hand-held darting gun and the backup weapon, the shoulder gun, have been used in the subsistence hunt since the 1880’s with only slight modifications until the advent of the Weapons Improvement Program in the early 1990s. The darting gun is mounted on a long wooden shaft to which a harpoon is also attached. The shoulder gun is a smooth-bore rifle weighing 35 pounds (16kg) and is used after the harpoon and float are attached to the whale.

Hunters assemble their umiak, harpoon, and darting gun along the ice edge in preparation for the hunt. Picture: Jenny Evans.

A hunter positions himself in the umiaq armed with a harpoon and darting gun. Picture: Jenny Evans.

Members of the WIP Committee travel to the AEWC’s villages, as funding allows, to train hunters in the safe use of the penthrite projectile and the associated equipment that delivers this very powerful explosive. The AEWC now is undertaking development of a new, standardized pusher shell to further increase the effectiveness of the penthrite projectile. Both the efficiency and effectiveness of the penthrite projectile are studied by the AEWC and scientists from the North Slope Borough. The United States, on behalf of the AEWC, reports regularly to the IWC’s Whale Killing Methods Working Group on the AEWC’s progress with the penthrite projectile and the WIP.

The WIP Committee provides training on the safe use of the penthrite projectile in Katktovik, AK (left) and Point Lay, AK (right). Picture: Billy Adams.

A great challenge to this program is the cost of the equipment. A single projectile costs approximately $1,000, an impossible amount for a subsistence hunter. While both the IWC and the U.S. Government encourage the use of the penthrite projectile in the bowhead harvest, neither has committed the funds to support the program in the long term, therefore, use of the new projectiles remains limited.

The AEWC reports, at each meeting of the IWC, on its work under this program. Reports submitted to the IWC on our Weapons Improvement Program are found in:

1993: A new penthrite grenade for the subsistence hunt of bowhead whales by Alaskan Eskimo – developmental work and field trials in 1988, Øen, E.O., (IWC/44/HKW/6)

1994: Hunting efficiency and recovery methods developed and employed by native Alaskans in the subsistence hunt of the bowhead whale, (IWC/46/HK/3)

1995a: Killing methods for minke and bowhead whales, Øen, E.O., (IWC/47/WK/8)

1995b: Hunting efficiency and recovery methods developed and employed by native Alaskans in the subsistence hunt of the bowhead whale, Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission, (IWC/47/WK/15)

1996: Determination of the muzzle velocity of the black powder and penthrite projectiles fired from a bench-mounted darting gun of the type used by Alaskan Eskimo in the subsistence hunt of the bowhead whale, as influenced by the propellant charge and other factors, Ingling, Allen, as submitted to the North Slope Borough.

1999: Hunting efficiency and recovery methods developed and employed by native Alaskas in the subsistence hunt of the Bowhead whale, (IWC/51/WK/4)

2000: Update on use of the penthrite projectile in the bowhead whale subsistence harvest at Barrow, Alaska, Dr. Todd O’Hara, (IWC/52/WKM & AWI/7)

2001: Report on the use of the penthrite grenade in the 2000 bowhead whale subsistence hunt in Barrow, Alaska, submitted by the U.S.A., (IWC/53/WKM & AWI/8)

2002: Report on the use of the penthrite projectile in the 2000 and 2001 bowhead whale subsistence hunts in Barrow, Alaska, submitted by the U.S.A., (IWC/54/WKM & AWI/9)

2003: Report on weapons, techniques and observations in the Alaskan bowhead whale subsistence hunt, submitted by the U.S.A., (IWC/58/WKM & AWI/22)

2004: Report of the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission Progress Concerning Improvement of Whale Killing Methods, submitted by U.S.A., (ref, Annual Report of the International Whaling Commission 2004, Annex G, p. 98)

2006: Report on Weapons, Techniques, and Observations in the Alaskan Bowhead Whale Subsistence Hunt, submitted by U.S.A. (IWC/58/WKM & AWI/22)

2007: Report on Weapons, Techniques, and Observations in the Alaskan Bowhead Whale Subsistence Hunt, submitted by U.S.A. (IWC/59/WKM & AWI/4)

2008: Report on Weapons, Techniques, and Observations in the Alaskan Bowhead Whale Subsistence Hunt, submitted by U.S.A.

2009: Report on Weapons, Techniques, and Observations in the Alaskan Bowhead Whale Subsistence Hunt, submitted by U.S.A. (IWC/61/WKM & AWI/4)

2010: Report on Weapons, Techniques, and Observations in the Alaskan Bowhead Whale Subsistence Hunt, submitted by U.S.A. (IWC/62/13)

2011: Report by Harry Brower, AEWC Chair, (Ref, IWC/63/Rep6)

2012: Report on Weapons, Techniques, and Observations in the Alaskan Bowhead Whale Subsistence Hunt, submitted by U.S.A. (IWC/64/WKM & AWI/8)

2014: Report on Weapons, Techniques, and Observations in the Alaskan Bowhead Whale Subsistence Hunt, submitted by U.S.A. (IWC/65/WKM & AWI/8)

2016: Report on Weapons, Techniques, and Observations in the Alaskan Bowhead Whale Subsistence Hunt, submitted by U.S.A. (IWC/66/WKM & AWI/4)

THE MOST RECENT IWC SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE ADVICE ON THE STATUS OF THE BERING-CHUKCHI-BEAUFORT SEAS STOCK OF BOWHEAD WHALES

The IWC requires a new abundance estimate every 10 years. The last ice-based abundance and Photo-ID-based surveys were conducted in 2011. The 2011 ice-based abundance estimate is 16,892 (within the range of 15,704 - 18,928). The rate of increase of the population, or trend, starting in 1979 was estimated to be 3.7 percent (within the range of 2.8 - 4.7 percent). These abundance and trend estimates show that the bowhead population is healthy and growing with a very low conservation risk under the current Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling management scheme.

At the IWC, the general approach used by the Scientific Committee to provide scientific advice to the Commission, for all ASW hunts, is through the use of a Strike Limit Algorithm (SLA). The first SLA was developed for the bowhead whale subsistence harvest in 2002 and has been used to provide management advice for the setting of bowhead whale harvest levels since 2003.

The IWC Scientific Committee integrates the available data (biology, ecology, abundance and trends, removals including direct hunting, ship strikes and bycatches, requested catches from the relevant ASW countries) to provide scientific advice to the Commission.

The most recent Scientific Committee advice (from the 2018 Scientific Committee meeting) for this population of bowhead whales is provided below. Note that the request for Scientific Committee advice on an annual strike limit of 67 whales is from the U.S. and that there is an agreement between the Russian Federation and the U.S. regarding the allocation of the catch limit between the two countries for their respective aboriginal subsistence whaling hunts (Alaska Natives and Chukotka Natives).

The USA indicated that it requested advice on the existing catch/strike limits. The Committee therefore:

(1) agrees that the Bowhead Whale SLA remains the best available way to provide management advice for this stock;

(2) advises that a continuation of the present average annual strike limit of 67 whales will not harm the stock and meets the Commission’s conservation objectives; and

(3) advises that provisions allowing for the carry forward of unused strikes from the previous three blocks, subject to the limitation that the number of such carryover strikes used in any year does not exceed 50% of the annual strike limit, has no conservation implications (see SC/67b/Rep04).

(Report of the Scientific Committee, Bled, Slovenia 24 April-6 May 2018 Item 8.3)

7. Information on Recent Catches

The Bowhead Whale Subsistence Quota

In addition to the general principles described in Schedule paragraph 13(a) under which aboriginal subsistence whaling catch limits shall be established, the current bowhead whale subsistence catch limits of Schedule paragraph 13(b) provide that:

(1) The taking of bowhead whales from the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort Seas stock by aborigines is permitted, but only when the meat and products of such whales are to be used exclusively for local consumption by the aborigines and further provided that:

(i) For the years 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018, the number of bowhead whales landed shall not exceed 336. For each of these years the number of bowhead whales struck shall not exceed 67, except that any unused portion of a strike quota from any year (including 15 unused strikes from the 2008-2012 quota) shall be carried forward and added to the strike quotas of any subsequent years, provided that no more than 15 strikes shall be added to the strike quota for any one year.

(ii) This provision shall be reviewed annually by the Commission in light of the advice of the Scientific Committee.

This level of harvest was first approved in 1997, more than 20 years ago, and has been shared between Alaska and Chukotka since that time. Aboriginal subsistence need has since increased, and the bowhead whale population estimate has almost doubled since this harvest level was approved.

2016 and 2017 Harvest Results

During 2016, 59 whales were struck; of those, 47 were landed and 12 were lost. The total number of whales struck and the total number landed in 2016 were higher than the average number of whales struck and the average number landed over the previous 10 years (2006-2015) during which the average struck was 54 and the average landed was 40. Harvest efficiency in 2016 was 79.7%, with an average over the 10 previous years of 74.1%.

During 2017, 57 whales were struck; of those, 50 were landed and seven were lost. The total number landed was higher than the average for the previous 10 years (2007-2016), during which the average landed was 42, with an average of 56 struck. Harvest efficiency in 2017 was 87.7%, with an average over the previous 10 years of 75%.

STEWARDS OF THE OCEAN

Expanding Uses of the Ocean

The AEWC’s work on management and conservation of the bowhead whale subsistence harvest goes beyond the specific duties set forth in the NOAA-AEWC Cooperative Agreement. The Arctic is changing and new activities and uses are appearing, with astonishing speed and frequency, in the habitat of the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort Seas stock of bowhead whales. Therefore, the whaling captains and Commissioners of the AEWC, working with our other hunter organizations, are taking responsibility for developing new processes and instituting new measures to protect the whale, its habitat, and the vital subsistence harvest.

Offshore Oil and Gas Development: Since the late 1970s, the U.S. and the State of Alaska have leased the nearshore waters of the Beaufort Sea for offshore oil and gas exploration and development. More recently, tracts in the Chukchi Sea have been opened to leasing as well. The exploration and development activity on these leaseholds brings large vessel traffic, seismic airguns, and industrial activity throughout much of the U.S. range of the bowhead whale and into subsistence harvest areas. To protect the whales, the hunters, and the harvest, the AEWC, since 1985, has worked with offshore operators through an annual private process known as the Open Water Season Conflict Avoidance Agreement (CAA). This process produces consensus measures that ensure that offshore oil and gas activities do not endanger hunters, interfere with migrating whales, or degrade whale habitat.

As the Arctic waters continue to open, increasing vessel traffic provides a challenge to subsistence hunters who rely on the resources from the sea for their survival. Picture: James Houck.

Arctic Shipping: With the retreat of arctic sea ice and increasing vessel traffic in northern Alaska’s waters, the AEWC, working with the U.S. Coast Guard, joined with others in 2012 to form the Arctic Waterways Safety Committee (AWSC). The AWSC is the largest Harbor Safety Committee in the U.S., by geographic area, and the only one that includes subsistence hunters among its members. As with the CAA, the AEWC’s goal in helping to create the AWSC and serving on the Committee is to protect the bowhead whale and its habitat, and to ensure the safety and ongoing success of our hunters.

Quyanakpak

Quyanakpak