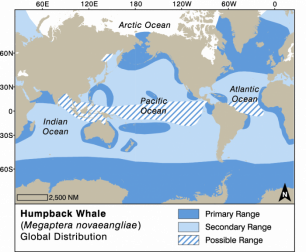

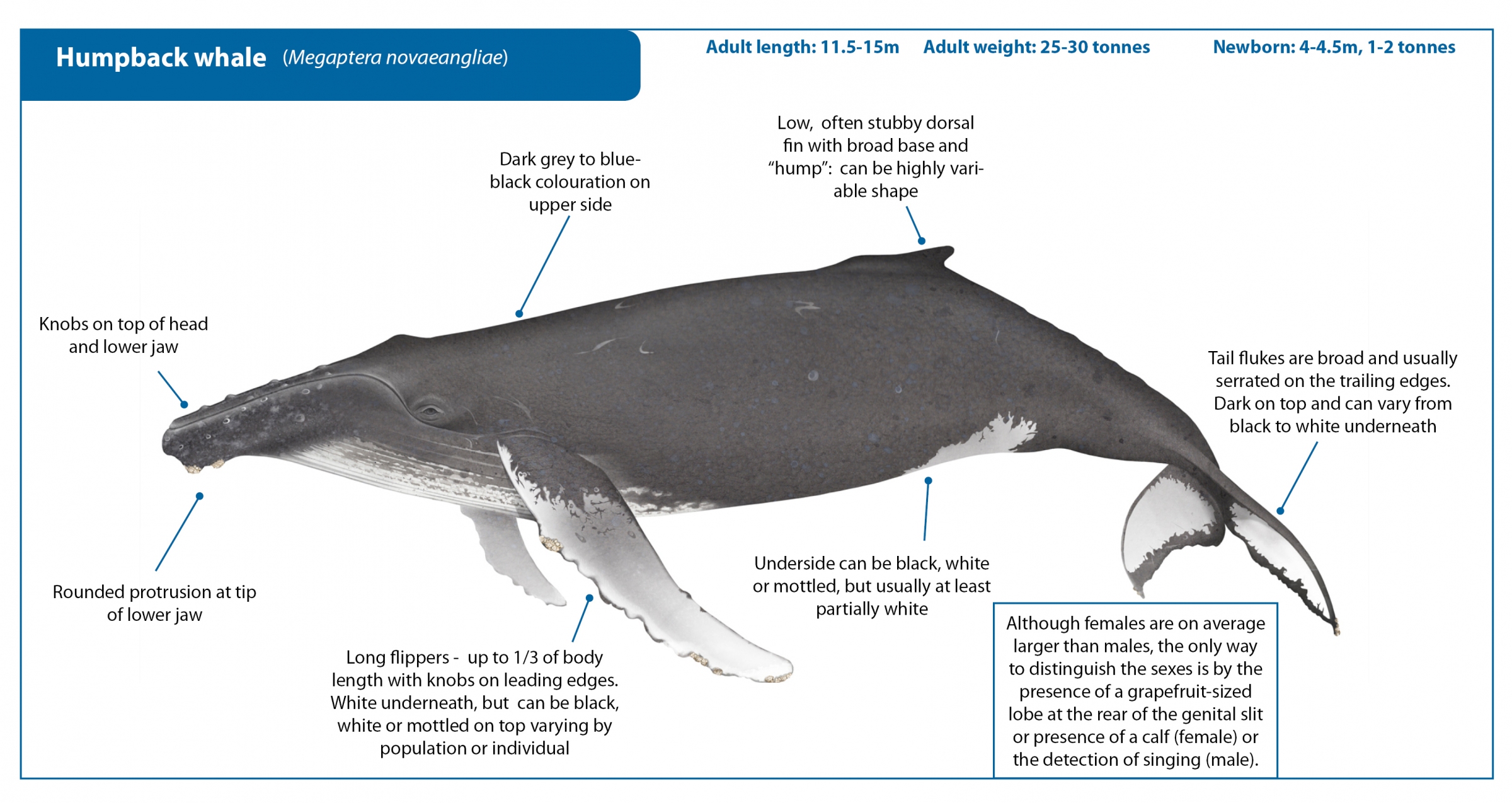

Humpback whales are one of the most-watched and well-studied species of whale. Found in every ocean and many nearshore areas associated with coastal and marine tourism, they are the focus of whale watching operations in over many countries around the world. The species is known for its spectacular “surface active behaviour”, which can include breaching (leaping clear of the water) and flipper and tail slapping, its occasional curiosity around tour boats, and its complex ‘song’, which is heard on the breeding grounds in the tropics. A humpback whale’s blow or the splash of a breach can be seen from a distance of several kilometres, making the humpback one of the more conspicuous targets of whale watching around the world. At close range, the species is unlikely to be confused with any other, due to the distinctive characteristics detailed below:

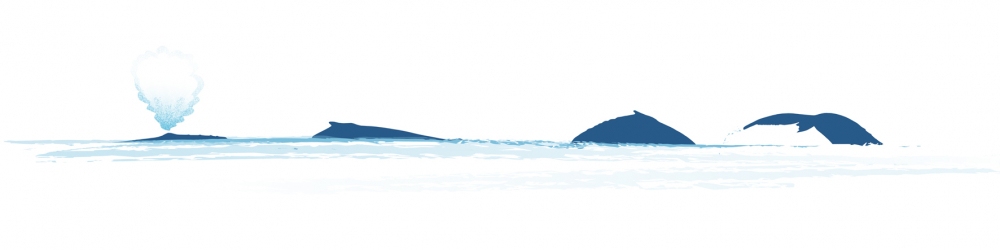

Humpback whale blow and surfacing pattern

Humpback whale blow and surfacing pattern

References

Show / Hide References

- Clapham, P. J. in Cetacean Societies (eds J. Mann, R.C. Connor, P.L. Tyack, & H. Whitehead) 173-196 (University of Chicago Press, 2000).

- Cerchio, S. et al. Satellite telemetry of humpback whales off Madagascar reveals insights on breeding behavior and long range movements within the Southwest Indian Ocean. MEPS 562, doi:10.3354/meps11951 (2016).

- Clapham, P. in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (eds W. Perrin, B. Wursig, & J.G.M. Thewissen) 582-584 (Elsevier, 2009).

- Ryan, C. et al. A longitudinal study of humpback whales in Irish waters. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 96, 877-883 (2016).

- Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Kerem, D. & Smeenk, C. Cetaceans of the Red Sea. CMS Technical series (In press).

- Genov, T., Kotnjek, P. & Lipej, L. New record of the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the Adriatic Sea. Annales ser. hist. nat. 19, 25-30 (2009).

- Minton, G. et al. Megaptera novaeangliae, Arabian Sea subpopulation. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species http://www.iucnredlist.org/det... (2008).

- Palsboll, P. J. et al. Genetic tagging of humpback whales Nature 388 767-769 (1997).

- Allen, J. M., Rosenbaum, H. C., Katona, S. K., Clapham, P. J. & Mattila, D. K. Regional and sexual differences in fluke pigmentation of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) from the North Atlantic Ocean. Canadian Journal of Zoology 72, 274-279 (1994).

- Murase, H., Matsuoka, K., Ichii, T. & Nishiwaki, S. Relationship between the distribution of euphausiids and baleen whales in the Antarctic (35§E - 145§W). 135-145 (2002).

- Fleming, A. H., Clark, C. T., Calambokidis, J. & Barlow, J. Humpback whale diets respond to variance in ocean climate and ecosystem conditions in the California Current. Global Change Biology, n/a-n/a, doi:10.1111/gcb.13171 (2015).

- Hain, J. H., Carter, G. R., Kraus, S. D., Mayo, S. A. & Winn, H. E. Feeding behaviour of the humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae, in the western north Atlantic. Fishery Bulletin 80, 259-268 (1982).

- Jurasz, C. M. & Jurasz, V. P. Feeding modes of the humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae, in Southeast Alaska. 31, 69-83 (1979).

- Findlay, K. P. et al. Humpback whale “super-groups” – A novel low-latitude feeding behaviour of Southern Hemisphere humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the Benguela Upwelling System. PLOS ONE 12, e0172002, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172002 (2017).

- Alves, L. C. P., Andriolo, A., Zerbini, A. N., Pizzorno, J. L. & Clapham, P. J. Record of feeding by humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in tropical waters off Brazil. Marine Mammal Science 25, 416-419 (2009).

- Barendse, J. et al. Migration redefined? Seasonality, movements and group composition of humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae off the west coast of South Africa. African Journal of Marine Science 32, 1-22 (2010).

- Thomas, P. O., Reeves, R. R. & Brownell, R. L. Status of the world's baleen whales. Marine Mammal Science, doi:10.1111/mms.12281 (2015).

- Pomilla, C. et al. The World's Most Isolated and Distinct Whale Population? Humpback Whales of the Arabian Sea. PLoS ONE 9, e114162, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0114162 (2014).

- Craig, A., Herman, L. M., Pack, A. A. & Waterman, J. O. Habitat segregation by female humpback whales in Hawaiian waters: avoidance of males? Behaviour 151, doi:10.1163/1568539x-00003151 (2014).

- Tyack, P. & Whitehead, H. Male competition in large groups of wintering humpback whales. Behaviour 83, 132-154 (1983).

- Winn, H. E. et al. Song of the humpback whale - population comparisons. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 8, 41-46 (1980).

- Gabriele, C. M. et al. Natural history, population dynamics, and habitat use of humpback whales over 30 years on an Alaska feeding ground. Ecosphere 8, e01641-n/a, doi:10.1002/ecs2.1641 (2017).

- Cerchio, S. et al. Satellite telemetry of humpback whales off Madagascar reveals insights on breeding behavior and long-range movements within the southwest Indian Ocean. Marine Ecology Progress Series 562, 193-209 (2016).

- Corkeron, P. J. & Connor, R. C. Why do baleen whales migrate? Marine Mammal Science 15, 1228-1245 (1999).

- Mehta, A. V. How important are baleen whales as prey for killer whales (Orcinus orca) in high-latitude waters? , Boston University, (2004).

- Mehta, A. V. et al. Baleen whales are not important as prey for killer whales Orcinus orca in high-latitude regions. Marine Ecology Progress Series 348, 297-307 (2007).

- Clapham, P. J. & Mead, J. G. Megaptera novaeangliae. Mammalian Species 604, 1-9 (1999).

- Clapham, P. J. et al. Catches of Humpback Whales, Megaptera novaeangliae, by the Soviet Union and Other Nations in the Southern Ocean, 1947–1973. Marine Fisheries Review 71 (2009).

- Doroshenko, N. V. Soviet catches of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the north Pacific Soviet Whaling Data (1949 - 1979), 48-95 (2000).

- Mikhalev, Y. A. Humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae in the Arabian Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series 149, 13-21 (1997).

- Reilly, S. et al. Megaptera novaeangliae. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species http://www.iucnredlist.org/det... (2008).

- NOAA. (eds National Oceanic and National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) & Commerce. Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)) 247 (Department of Commerce, Washington DC, USA, 2016).

- IWC. Report of the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission 2016: Annex H: Report of the Sub-Committee on Other Southern Hemisphere Whale Stocks. 44 (International Whaling Commission, Bled, Slovenia, 2016).

- Scheidat, M., Castro, C., Gonzalez, J. & Williams, R. Behavioural responses of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) to whalewatching boats near Isla de la Plata, Machalilla National Park, Ecuador. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 6, 63-68 (2004).

- Stamation, K. A., Croft, D. B., Shaughnessy, P., Waples, K. A. & Briggs, S. V. Behavioral responses of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) to whale-watching vessels on the southeastern coast of Australia. Marine Mammal Science 26, 98 - 122 (2010).

- Weinrich, M. & Corbelli, C. Does whale watching in Southern New England impact humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) calf production or calf survival. Biological Conservation 142, 2931–2940 (2009).

- Andriolo, A., Kinas, P., Engel, M., Martins, C. & Rufino, A. Humpback whales within the Brazilian breeding ground: distribution and population size estimate. Endangered Species Research 11, 233–243 (2010).