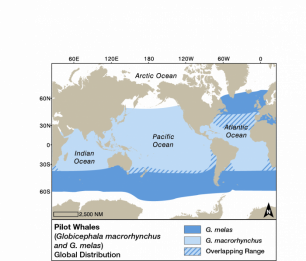

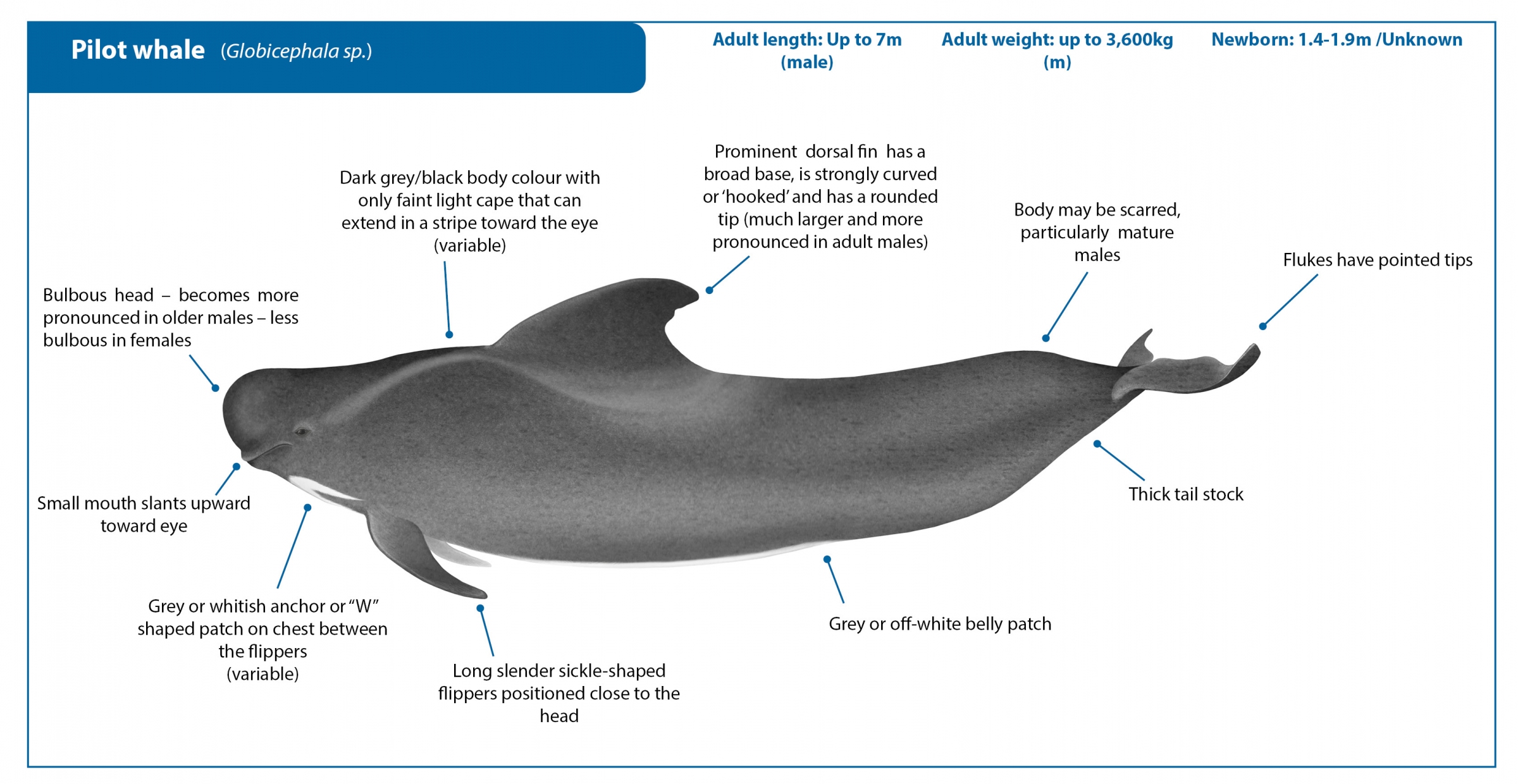

Pilot whales are so named because it was once believed that each observed group was navigated by a pilot or leader. Their Latin name, Globicephala, means ‘round head’, which is one of the main identifying features of the species. The bulbous head and thick curved dorsal fin become even more pronounced in adult males, who become easy to distinguish from females and juveniles. While normally oceanic in their distribution, pilot whales can also approach coastal areas, and are frequently seen on whale watching tours around the world. They are rewarding to watch, as they are generally approachable and impressive in size and behaviour. There are two species of pilot whales: Short finned pilot whales (Globicephala macrorhynchus), which are mainly found in tropical and warm-temperate regions, and long-finned pilot whales (G. melas), which inhabit colder waters and are further subdivided into three sub-species: the Southern long-finned pilot whale (G. m. edwardii), the North Atlantic long-finned pilot whale (G. m. melas), and the now extinct North Pacific long-finned pilot whale (G. m. un-named subsp.)1.

References

Show / Hide References

- Committee on Taxonomy, List of marine mammal species and subspecies. Society for Marine Mammalogy, www.marinemammalscience.org, consulted on 11 October 2017. 2017.

- Olson, P.A., Pilot Whales, Globicephala melas and G. macrorynchus, in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, W. Perrin, B. Wursig, and J.G.M. Thewissen, Editors. 2009, Elsevier: San Francisco. p. 847-852.

- Olson, P.A., Pilot Whales, Globicephala melas and G. macrorhynchus, in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, B. Würsig, J.G.M. Thewissen, and K.M. Kovacs, Editors. 2017 Academic Press, Elsevier: San Diego. p. 701-705.

- Taylor, B.L., et al., Globicephala melas, in IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008, http://www.iucnredlist.org/det... Consulted on 9 October 2017.

- Jefferson, T.A., M.A. Webber, and R.L. Pitman, Marine Mammals of the World: a Comprehensive Guide to their Identification. Second Edition. 2015: San Diego: Academic Press.

- Werth, A., A kinematic study of suction feeding and associated behavior in the long-finned pilot whale, Globicephala melas (Traill). Marine Mammal Science, 2000. 16(2): p. 299-314.

- Cañadas, A. and R. Sagarminaga, The northeastern Alboran Sea, an important breeding and feeding ground for the long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas) in the Mediterranean Sea. Marine Mammal Science, 2000. 16(3): p. 513-529.

- Baird, R.W., False Killer Whale, Pseudorca crassidens, in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, W. Perrin, B. Wursig, and J.G.M. Thewissen, Editors. 2009, Elsevier: San Francisco. p. 405-406.

- Chambers, S. and R. James, Sonar termination as a cause of mass cetacean strandings in Geographe Bay, south-western Australia. Proceedings of ACOUSTICS 2005, 2005: p. 9-11.

- Vanselow, K.H., et al., Solar storms may trigger sperm whale strandings: explanation approaches for multiple strandings in the North Sea in 2016. International Journal of Astrobiology, 2017: p. 1-9.

- Oremus, M., et al., Genetic Evidence of Multiple Matrilines and Spatial Disruption of Kinship Bonds in Mass Strandings of Long-finned Pilot Whales, Globicephala melas. Journal of Heredity, 2013. 104(3): p. 301-311.

- 1Taylor, B.L., et al., Globicephala macrorhynchus, in IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008, http://www.iucnredlist.org/det... Consulted on 9 October 2017.

- Mignucci-Giannoni, A.A., et al., Cetacean strandings in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. 1998. p. 1-8.

- Gajdosechova, Z., et al., Possible link between Hg and Cd accumulation in the brain of long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas). Science of The Total Environment, 2016. 545-546: p. 407-413.

- NAMMCO. Report of the Meeting of the Management Committee for Cetaceans, March 2018. 17 (North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission Tromsø, Norway, 2018).

- Kasuya, T. Small Cetaceans of Japan: Exploitation and Biology. 476 (CRC Press, 2017).

- Fielding, R. & Evans, D. W. Mercury in Caribbean dolphins (Stenella longirostris and Stenella frontalis) caught for human consumption off St. Vincent, West Indies. Marine Pollution Bulletin 89, 30-34, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marp... (2014).

- Emont, J. in The New York Times Vol. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/03/world/asia/whaling-lamalera-indonesia.html Onlne (New York, New York, 2017).

- Mustika, P. L. K. Marine Mammals in the Savu Sea (Indonesia); indigenous knowledge, threat analysis and management options BSc(Hons) Thesis thesis, James Cook University, (2006).

- Jensen, F. H. et al. Vessel noise effects on delphinid communication. Marine Ecology Progress Series 395, 161-175 (2009).