The increasing amount of debris in the world's oceans has become a major cause for concern. There are many different types of marine debris. It travels freely and does not recognise national boundaries, which means international collaboration is essential to any attempts to address the issue effectively.

Marine debris ranges from glass, metal, plastics and wood to abandoned or lost fishing gear. Much is synthetic and estimated to endure for up to 600 years. Different materials can threaten cetaceans, and other marine life in different ways. The IWC is working through a number of programmes to understand and mitigate potential threats from a range of different types of debris. In 2022 the Commission endorsed a Resolution on Marine Plastic Pollution. Activity set out in the Resolution includes increased collaboration and cooperation with relevant international organisations and Scientific Committee work towards identifying hotspots of cetacean exposure to plastic debris.

Three marine debris workshops have already taken place, bringing together experts from a range of relevant fields. The first, was scientifically focused, analysing the different threats, knowledge gaps and further research requirements. The second workshop was policy-led, agreeing practical, management actions that the IWC could take in order to contribute its expertise most effectively to the each of the range of global initiatives on marine debris. The third reviewed the latest evidence of ingestion, entanglement, microdebris and toxicology.

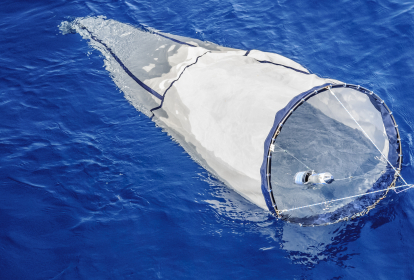

Much work is still to do, but some progress has already been made, particularly in addressing the threat of large whale entanglement in fishing gear, including lost and abandoned gear. Since 2012, the IWC has managed an entanglement response capacity building programme. Experienced IWC member governments share experience and best practice with other countries looking to establish a safe and effective response capability. Training workshops also teach consistent data collection techniques, and the data supplied from responders will be used to improve understanding of the types of fishing gear and debris that pose the greatest threat, in order to develop alternatives.

Ingestion of items of debris is another potential threat. Recent research suggested that examples of ingestion have been found for just over half of cetacean species although more work is required to understand better the nature of the threat, the numbers involved and the level of threat at a population level. Perhaps unsurprising given its endurance, plastic is the most commonly detected ingested material recorded.

Microplastics can be ingested directly and also potentially transferred from prey species (krill and copepods) to whales where their accumulation may pose a health threat. As part of its work on pollution, the Scientific Committee is studying the origin, fate and distribution of microplastics.

Reports

-

Report of the 2019 workshop on marine debris

-

Report of the 2014 workshop on marine debris

-

Report of the 2013 workshop on marine debris

Further reading