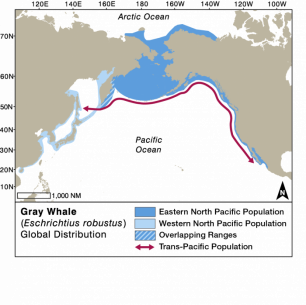

Some of the first whale watching tours ever to have been offered focused on gray whales along the coast of southern California. Found close to shore, and often curious around boats, the species is well-loved by whale watchers up and down the west coasts of Canada, the United States and Mexico. Here, in the eastern part of its range, the species seems to have recovered after protection from whaling. However, the western gray whale subpopulation that feeds near Russia’s Sakhalin Island and Kamchatka Peninsula in the eastern Pacific is one of the smallest whale populations in the world.

Gray whale surfacing and dive pattern

Download Gray Whale A4 Factsheet

References

Show / Hide References

- Jones, M. L. & Swartz, S. in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (eds W. Perrin, B. Wursig, & J.G.M. Thewissen) 503-511 (Elsevier, 2009).

- Mate, B. R. et al. Critically endangered western gray whales migrate to the eastern North Pacific. Biology Letters

11, doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0071 (2015). - Weller, D. W. et al. Movements of gray whales between the western and eastern North Pacific. Endangered Species Research

18, 193-199 (2012). - Dunham, J. S. & Duffus, D. A. Foraging patterns of gray whales in central Clayoquot Sound, British Columbia, Canada Marine Ecology Progress Series

223, 299-310 (2001). - Woodward, B. L. & Winn, J. P. Apparent Lateralized behaviour in Gray Whales feeding off the Central British Columbia coast. Marine Mammal Science

22, 64-73 (2006). - LeDuc, R. G. et al. Genetic differences between western and eastern North Pacific gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus). Journal of Cetacean Research and Management

4, 1-5 (2002). - Cooke, J. G. et al. Updated population assessment of the Sakhalin gray whale aggregation based on the Russia-US photoidentification study at Piltun, Sakhalin, 1994-2014. 11 (Western Gray Whale Advisory Panel Doc. WGWAP/16/17, 2015).

- Perryman, W. L., Donahue, M. A., Perkins, P. C. & Reilly, S. B. Gray whale calf production 1994-2000: Are observed fluctuations related to changes in seasonal ice cover? Marine Mammal Science

18, 121-144 (2002). - Hoyt, E. Whale Watching 2001: Worldwide tourism numbers, expenditures and expanding socioeconomic benefits. 1-256 (International Fund For Animal Welfare, London, 2001).

- Heckel, G., Reilly, S. B., Sumich, J. L. & Espejel, I. The influence of whalewatching on the behaviour of migrating gray whales (Eschrictius robustus) in Todos Santos Bay and surrounding waters, Baja California, Mexico. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management

3, 227-238 (2001).