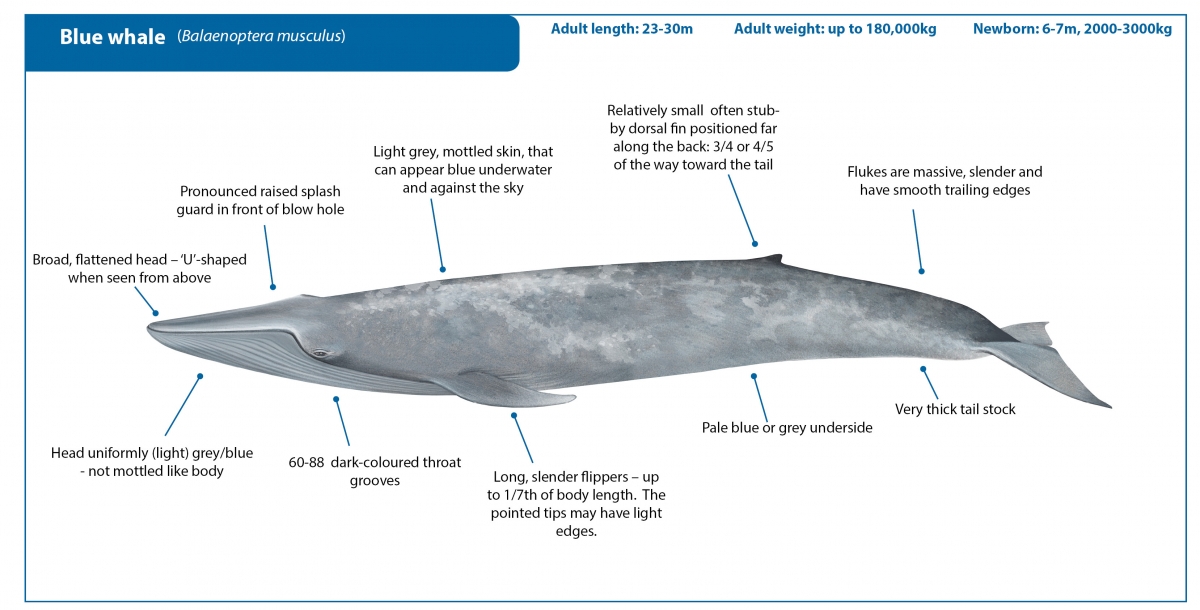

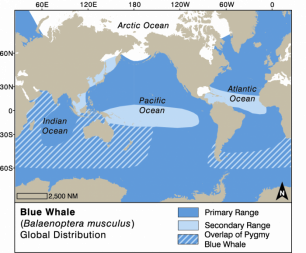

The largest animals ever to have lived on the planet (surpassing even dinosaurs), blue whales inspire awe and wonder with all the records they break: The largest blue whale ever recorded was 33 m long; a blue whale’s heart is the size of a small car; a child could crawl through a blue whale’s arteries; and blue whales produce the loudest sound on earth – even if it is too low in frequency for humans to hear it. There are at least five recognized sub-species of blue whale that occur in different ocean basins.

References

Show / Hide References

- Sears, R. & Perrin, W. F. in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (eds W. Perrin, B. Wursig, & J.G.M. Thewissen) 121-124 (Elsevier, 2009).

- Branch, T. A. et al. Past and present distribution, densities and movements of blue whales Balaenoptera musculus in the Southern Hemisphere and northern Indian Ocean. Mammal Review 37, 116-175 (2007).

- Gendron, D. Population Ecology of the Blue Whales, Balaenoptera musculus, of the Baja California Peninsula PhD thesis, (2002).

- Calambokidis, J. & Barlow, J. Abundance of blue and humpback whales in the Eastern North Pacific estimated by capture-recpature and line-transect methods. Marine Mammal Science 20, 63-85, doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2004.tb01141.x (2004).

- Redfern, J. et al. Assessing the Risk of Ships Striking Large Whales in Marine Spatial Planning. Conservation Biology 27, 292-302 (2013).

- Redfern, J. V. et al. Predicting cetacean distributions in data-poor marine ecosystems. Diversity and Distributions, n/a-n/a, doi:10.1111/ddi.12537 (2017).

- Jefferson, T. A., Webber, M. A. & Pitman, R. L. Marine Mammals of the World: a Comprehensive Guide to their Identification. Second Edition. (San Diego: Academic Press, 2015).

- de Vos, A., Brownell, R., Tershy, B. & Croll, D. Anthropogenic Threats and Conservation Needs of Blue Whales, Balaenoptera musculus indica, around Sri Lanka. Journal of Marine Biology 2016 (2016).

- McKenna, M. F., Calambokidis, J., Oleson, E. M., Laist, D. W. & Goldbogen, J. A. Simultaneous tracking of blue whales and large ships demonstrates limited behavioral responses for avoiding collision. Endangered Species Research 27, 219-232 (2015).

- Thomas, P. O., Reeves, R. R. & Brownell, R. L. Status of the world's baleen whales. Marine Mammal Science, doi:10.1111/mms.12281 (2015).

- Branch, T. A., Matsuoka, K. & Miyashita, T. Evidence for increases in Antarctic blue whales based on Bayesian modelling Marine Mammal Science 20, 726-754, doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2004.tb01190.x.

-

Branch, T. A., Matsuoka, K. & Miyashita, T. Evidence for increases in Antarctic blue whales based on Bayesian modelling. Marine Mammal Science 20, 726-754 (2004).